“It is not two years since the sight of a person who had lost one of his lower limbs was an infrequent occurrence. Now, alas! There are few of us who have not a cripple among our friends, if not in our own families. A mechanical art which provided for an occasional and exceptional want has become a great and active branch of industry. War unmakes legs, and human skill must supply their places as it best may.”

~Oliver Wendell Holmes, M.D., “The Human Wheel, Its Spokes and Felloes”

If necessity is the mother of invention, it should come as no surprise that the Civil War, which produced some 45,000 amputee veterans, also prompted major progress in the development and production of artificial limbs. One of the characters in my novel Widow of Gettysburg is the recipient of one of these limbs.

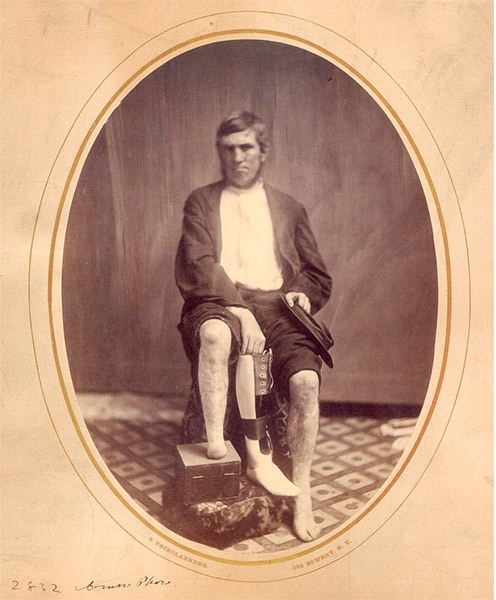

Let’s take a closer look at what was involved in this rehabilitation of amputee veterans. (You can see more on amputations in a previous blog post, here.) Once the stump was healed after amputation and the patient able to do without dressings, the surgeons' work was finished, and the patient was left to shift for himself in securing the best apparatus. But not everyone was a good candidate for a prosthetic. If the limb was taken off at the joint, such as the hip or shoulder, there was no stump to which an artificial limb could be attached. The surgeon may have performed the operation too high or too low on the limb for a good fit to be possible. Also, if the stump was prone to frequent infection, it would have been too painful to attach an artificial limb to it.

For those who could pursue a prosthetic, in the North, the most popular artificial leg was a “Palmer” leg, named for Benjamin Franklin Palmer, who patented the design. A previous design by James Potts was made of wood, leather, and cat-gut tendons hinging the knee and ankle joints, and dubbed “The Clapper” for the clicking sound of its motion. Palmer improved upon this design with a heel spring in 1846, and his “American leg” was produced continuously through World War 1. Palmer’s leg cost about $150, a prohibitive amount for the average private, whose pay was about $13 per month. Add to that the cost of travel and lodging expenses to see a specialist, and the number of amputees who could afford it went down even further. The cost of an artificial limb for Confederate veterans was between $300-$500, due to the soaring inflation.

Since the majority of veterans had been farmers, planters, or skilled laborers before the war, the need for artificial limbs was, indeed, a crippling problem. To help address it, the U.S. government appropriated $15,000 in 1862 to pay for limbs for maimed soldiers and sailors. In January 1864, a civilian association in Richmond was established to pay for artificial limbs for Confederate amputees. After the war in 1866, North Carolina became the first state to start a program for thousands of amputees to receive artificial limbs. The program offered veterans free accommodations and transportation by rail; 1,550 veterans contacted the program by mail. During the same year, the State of Mississippi spent more than half its yearly budget providing veterans with artificial limbs.

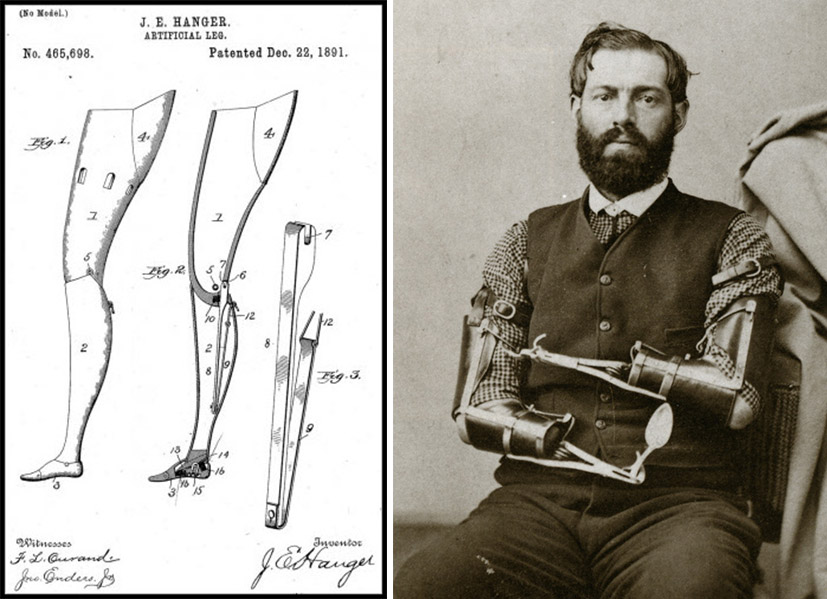

Many entrepreneurs who developed artificial limbs were Civil War veteran amputees themselves. In fact, one of the most successful pioneers in prosthetics was Confederate veteran James Edward Hanger, whose amputation in West Virginia was the first recorded amputation of the Civil War. He was 18 years old at the time. Union surgeons discovered him wounded and performed the amputation, giving him a standard issue replacement leg: a solid piece of wood that made walking clunky and difficult. Hanger’s adjustments included better hinging and flexing abilities using rust-proof levers and rubber pads. He also used whittled barrel staves to make the limb lighter-weight. He won the Confederate contract to produce limbs, and by 1890, had moved his headquarters to Washington, D.C., and opened satellite offices in four other cities. The company he founded – Hanger, Inc. – remains a key player in prosthetics and orthotics today. The Civil War-era commitment to support veterans continues today through programs of the VA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to ensure ongoing progress in prosthetics design. The war set the prosthetics industry on a course that would ultimately lead to today’s quasi-bionic limbs that look like the real thing and can often perform some tasks even better.

For further reading: Hasegawa, Guy R. Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs. Southern Illinois University Press, 2012.

Add new comment