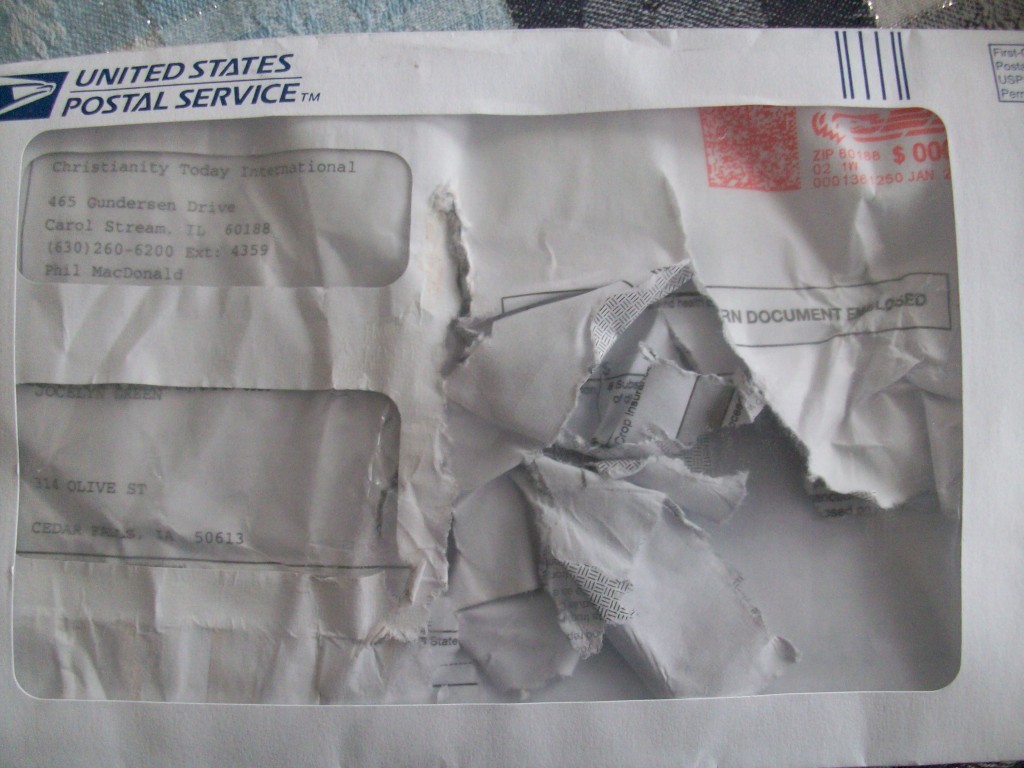

Yesterday I received a fairly mangled piece of mail—not a car dealership ad, either, which would have been promptly recycled anyway. This was a tax document.

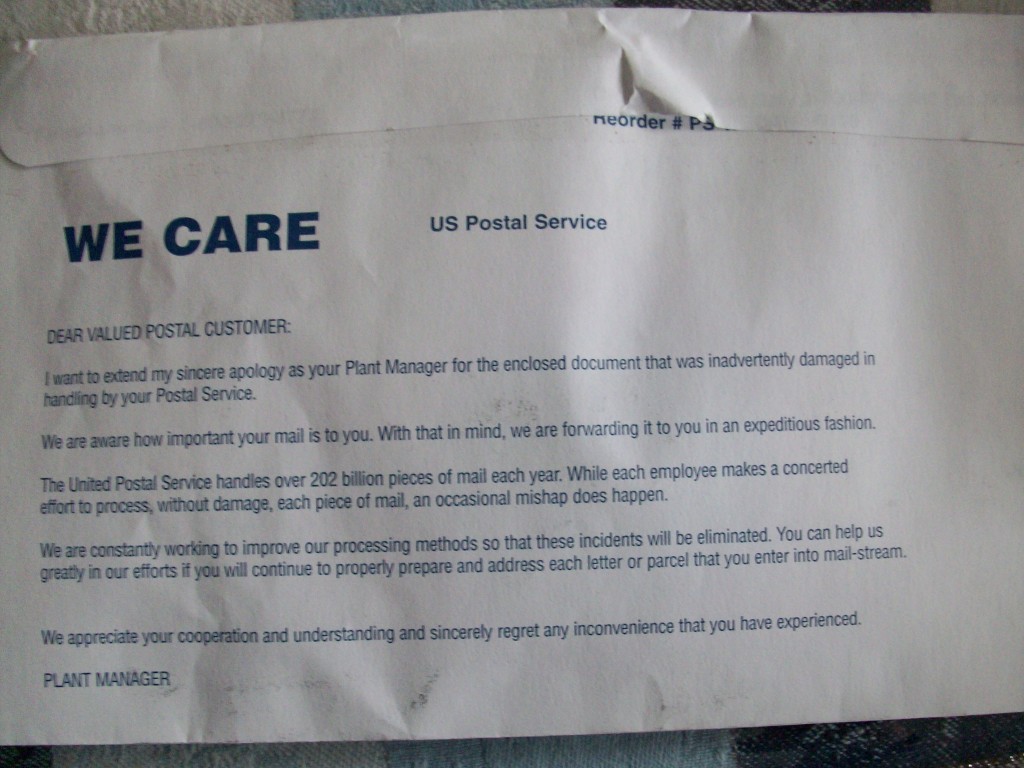

But then I flipped over the envelope containing the remains, and after scanning the text, simply thought, “Huh. That’s nice of the post office. They’re trying. They care,” and then went to make a cup of tea. (I do that a lot during the winter, living here in Iowa.)

Two days ago, I would have been just a little irked about the torn up document. But it’s what I read in my research for novel #3 just before the mail arrived that totally put my mail mishap into perspective.

The Civil War didn’t just divide the country, it divided families—not just politically and ideologically, but geographically. Regardless of their views on the war, relatives in both North and South longed to see each other. That was virtually impossible, as travelling across the lines required a passport, and officials on both sides denied about 90 percent of those requests.

Sending transsectional letters was an option, but mail crossing the lines had to carry both Union and Confederate postage, it had to contain the full names of the recipients and senders, and the content had to be limited to family matters. Even mentioning that your property had been raided or destroyed was considered contraband, because it related to the war. All transsectional mail went through Fort Monroe, Virginia, where it was inspected. The inspectors could censor your letters, or choose not to send them at all. Mail that did make it through could take a few weeks or up to a year to reach its destination. Some personal mail was even published in newspapers as “special reports” from far-away locations.

Can you imagine? Clearly, this system was not working.

Then in December of 1863, someone had the brilliant idea of purchasing space in the advertising section of the New York Daily News to send a message to a distant relative who may read the paper. Others caught on, and within a month, the New York Daily News and the Richmond Enquirer had an arrangement whereby they reprinted each other’s ads so family members North and South could finally communicate in a reliable manner.

Two dollars would buy eight lines of space. Here are some family advertisements that ran:

"Edward C. Huntley, Richmond, Va.—Folks all well; no news from Kate; Aunt Sarah dead; money in bank for you, Holmes, Executor; I am keeping hotel at Catskill. Have started twice to see you; couldn’t get there. Heard from you some time ago, and answered per directions. Let us hear from you again. JACK."

Another Southerner published:

“Lost all my children to yellow fever. Kate and I are well.”

A notice to a Union brother:

“Dear Brother. I am well, but have been severely wounded twice. Father and brother William died during the siege of Vicksburg…Would like to hear from you.”

In a single issue of the Richmond Enquirer, more than 100 ads could run, filling five columns and more than one full page of the paper. More than 2000 family advertisements appeared in 1864.

By the end of the year, however, war officials decided this had to stop, and put an end to it. Why? According to their logic, either 1) the ads contained coded messages of espionage or 2) the families were benefiting from encouragement from their relatives, which made them better able to persevere in the war. The war officials on the Union side would rather see Southerners demoralized enough to hasten a surrender. Sad but true.

So my mangled mail really doesn’t bother me. When I think about how hard it was for these families to communicate, it makes me very grateful for all the ways I have of communicating, even with by brother and sister-in-law who live in France.

In fact, I think I’ll write to them today, and marvel that at the click of my mouse, they will get my email in mere moments.

Who will you write to today, just because you can?

SOURCE: The Divided Family in Civil War America by Amy Murrell Taylor. The University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Comments

Add new comment