Civil War Christmas Song: I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day!

Four years ago, I shared this poignant Christmas song on the blog, in the wake of the shooting at Sandy Hook, and the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. But now in 2016, the words are just as meaningful as ever. It's been a long, hard year, hasn't it? And if there is anything that personal or national hardships teach us, it's the simple fact that we need a Savior. This Christmas, as we celebrate Jesus' birth, may we remember that Immanuel, God with us, is still here.

The Christmas song "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day" is a powerful reminder of that truth, with words by Henry Longfellow, and music by John Calkin. The lyrics were first penned in the midst of the horrors of our Civil War, a song which seems especially fitting this year. God is not dead, nor does he sleep... Take a moment to enjoy Casting Crowns rendition of this classic song below.

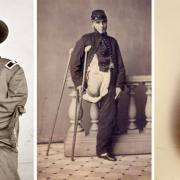

Now let's scroll back in time and take a look at how this song was born. During the Civil War, the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was informed by a letter dated March 14, 1863, that his oldest son Charles Appleton Longfellow had left home to join the Union army--without Henry's blessing. The letter said, in part: "I have tried hard to resist the temptation of going without your leave but I cannot any longer," he wrote. "I feel it to be my first duty to do what I can for my country and I would willingly lay down my life for it if it would be of any good." By November, he was severely wounded in the Battle of New Hope Church (in Virginia) during the Mine Run Campaign. Coupled with the recent loss of his wife Frances, who died as a result of an accidental fire, Longfellow was inspired to write "Christmas Bells" on Christmas Day, 1863. Henry's personal tragedy was wrapped in the national tragedy of the nation's civil war. The lyrics are below. The fourth and fifth verses you'll find here refer directly to the Civil War and are usually left out of the traditional Christmas song.

I heard the bells on Christmas day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet the words repeat

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along the unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

Till ringing, singing on its way

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime, a chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South, And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head

“There is no peace on earth,” I said,

“For hate is strong and mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good will to men.”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail

With peace on earth, good will to men.”

The hope Longfellow found among crisis can still be ours today.

"For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be uponhis shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and of peace there will be no end, on the throne of David and over his kingdom, to establish it and to uphold it with justice and with righteousness from this time forth and forevermore. The zeal of the Lord of hosts will do this" (Isiaha 9:6-7).

Merry Christmas!