Today in Civil War History: The Gettysburg Address

Confession: I get more excited about the anniversary of the Gettysburg Address every year than I do for my own birthday. Happy Dedication Day everyone! On this day in 1863, an estimated 15,000 attended the Dedication Ceremony of the National Soldiers Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a little more than four months after the battle of Gettysburg took place. The National Cemetery wasn't quite ready by this date yet, however, so the actual ceremony took place about fifty yards away at Evergreen Cemetery. For more about what this momentous day was like, here's a brief video from historian Tim Smith and Civil War Trust.

The keynote speaker for Dedication Day was the politician and orator Edward Everett, who spoke for two hours, while Abraham Lincoln's speech was closer to two minutes.

Read the text of Edward Everett's speech here.

Read Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg address here.

[[{"type":"media", "view_mode":"media_large", "fid":"918", "attributes":{"class":"media-image size-full wp-image-2572", "typeof":"foaf:Image", "style":"", "width":"550", "height":"547", "alt":"Painting: Gettysburg Address by Mort Kunstler"}}]] Painting: Gettysburg Address by Mort Kunstler

A few observations from Gettysburg residents follow.

"[The president was] the most peculiar looking figure on horseback I had ever seen. He rode a medium-sized black horse and wore a black high silk hat. It seemed to be that his feet almost touched the ground, but he was perfectly at ease." ~Daniel Skelly

"The chief impression made on me...was the inexpressible sadness on his face, which was in so marked contrast with what was going on...where all was excitement and where everyone was having such a jolly time [referring to a parade before the speeches]." ~Liberty Hollinger

[[{"type":"media", "view_mode":"media_large", "fid":"919", "attributes":{"class":"media-image alignleft size-full wp-image-2568", "typeof":"foaf:Image", "style":"", "width":"300", "height":"239", "alt":"lincoln address"}}]]In the text of his address, Lincoln said, "The world will little note nor long remember what we say here," but has been proven wrong for 151 years. After Lincoln's remarks, his Attorney General, Wayne McVeagh, told him, "You have made an immortal address!" Lincoln was quick to respond: "Oh, you must not say that. You must not be extravagant about it." McVeagh, however, had it right. Lincoln's words continue to inspire. Personally, I wish I could have been at Gettysburg last year for the 150th anniversary. (But since I was able to be present for the 150th anniversary of the battle in July 2013, I have no room to complain!) Fortunately for me, and for everyone else who would have liked to have been there for last year's Dedication Day, we can watch the ceremony in its entirety below, thanks to the Gettysburg Foundation. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell and Pulitzer Prize-winning historian James McPherson were the keynote speakers at Soldiers' National Cemetery, Gettysburg National Military Park. The program included a naturalization ceremony for 16 new citizens administered by officials from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; remarks by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett; a reading of the Gettysburg Address by Lincoln portrayer James Getty; musical performances by the U.S. Marine Band and others; and a Civil War color guard presented by the 11th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Fife and Drum. Enjoy!

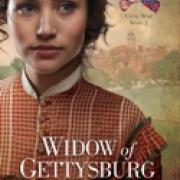

The final scene of my novel Widow of Gettysburg takes place at the Dedication Ceremony, Nov. 19, 1863. Can you think of any other movies or books in which the characters are inspired by or quote Lincoln's Gettysburg Address? Why do you suppose this two-minute speech is still so powerful today?

Source for quotes in this blog post: Bennett, Gerald R. Days of Uncertainty and Dread: The Ordeal Endured by the Citizens at Gettysburg. Gettysburg, PA: The Gettysburg Foundation, 1994.

About Widow of Gettysburg

When a horrific battle rips through Gettysburg, the farm of Union widow Liberty Holloway is disfigured into a Confederate field hospital, bringing her face to face with unspeakable suffering--and a Rebel scout who awakens her long dormant heart.

While Liberty's future crumbles as her home is destroyed, the past comes rushing back to Bella, a former slave and Liberty's hired help, when she finds herself surrounded by Southern soldiers, one of whom knows the secret that would place Liberty in danger if revealed.In the wake of shattered homes and bodies, Liberty and Bella struggle to pick up the pieces the battle has left behind. Will Liberty be defined by the tragedy in her life, or will she find a way to triumph over it?

Widow of Gettysburg is inspired by first-person accounts from women who lived in Gettysburg during the battle and its aftermath. Read more about the inspiration of the novel here. This is the second novel in Jocelyn Green's Heroines Behind the Lines series. Check out the brief book trailer below: