5 Pioneering Women Doctors and Nurses of the Civil War

The truth is, all women who were doctors and nurses during the Civil War were pioneers in their field. Prior to 1861, nurses--and all but two doctors in the United States--were men. But when social reformer Dorothea Dix pointed out to President Lincoln that he had a scant 28 surgeons in the army's medical department to care for the 75,000 volunteers he'd just called for, he reluctantly conceded that women be allowed to serve as nurses. I want to introduce you to five remarkable women who blazed the trail for women in medicine.

1) Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell. An English immigrant, Dr. Blackwell (shown at left) was the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States, and ran an infirmary for women and children near the slums of New York City. When the Civil War broke out, she realized the Union army needed a system for distributing supplies and organized four thousand women into the Women’s Central Association of Relief (WCAR). The WCAR grew into chapters around the county, and this body systematically collected and distributed life-saving supplies such as bandages, blankets, food, clothing and medical supplies. Blackwell also partnered with several prominent male physicians in New York City to offer a one-month training course for 100 women who wanted to be nurses for the army. This was the first formal training for women nurses in the country. Once they completed their training, they were placed at various hospitals. By July 1861, the WCAR prompted the government to form a national version—the United States Sanitary Commission. And it all started because Dr. Blackwell decided to mobilize the women of the country to help the Union.

Georgeanna Woolsey

2) Georgeanna Woolsey. At 28 years old, Georgeanna should not have been allowed to serve the army as a nurse, but she got through the application process anyway. Against her mother’s and sisters’ wishes, she was one of the 100 women trained in New York City to be a nurse. Not content to sit in a parlor and knit or scrape lint, she was eager to go where the fighting was, to get her hands dirty in a way she had never been allowed to before as a wealthy, privileged woman. Georgeanna wrote many letters and accounts of her experiences, including this:

“Some of the bravest women I have ever known were among this first company of army nurses. . . . Some of them were women of the truest refinement and culture; and day after day they quietly and patiently worked, doing, by order of the surgeon, things which not one of those gentlemen would have dared to ask of a woman whose male relative stood able and ready to defend her and report him. I have seen small white hands scrubbing floors, washing windows, and performing all menial offices. I have known women, delicately cared for at home, half fed in hospitals, hard worked day and night, and given, when sleep must be had, a wretched closet just large enough for a camp bed to stand in. I have known surgeons who purposely and ingeniously arranged these inconveniences with the avowed intention of driving away all women from their hospitals. “These annoyances could not have been endured by the nurses but for the knowledge that they were pioneers, who were, if possible, to gain standing ground for others. . ."

Georgeanna Woolsey is the inspiration for my main character in Wedded to War. Woolsey nursed patients in seminary buildings, the U.S. Patent Office, and aboard hospital transport ships which carried wounded and sick soldiers from the swamps of the Virginia Peninsula. After the war, Georgeanna and her husband, veteran Union surgeon Dr. Francis

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker

Bacon, founded the Connecticut Training School for Nurses at New Haven Hospital. She also published Hand Book of Nursing for Family and General Use and co-founded the Connecticut Children's Aid Society.

3) Dr. Mary Edwards Walker After volunteering as a nurse in 1861, and then as an assistant surgeon, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker earned a Union army commission for her services as surgeon in 1863. In 1864, she was captured by Confederates, suspected of espionage, and thrown into Richmond's Castle Thunder prison where she remained four months before her release. In 1865, she became the only woman ever to receive the Medal of Honor. Dr. Walker appears in Spy of Richmond. The newspaper article Mr. Kent dictates to Sophie about Dr. Walker's imprisonment is verbatim from the original story that ran in the Richmond Enquirer--including the comment about her "homely" appearance.

4) Captain Sally Tompkins Sally Louisa Tompkins founded a private hospital in Richmond, Virginia, to care for the flood of Confederate wounded. During the war, her hospital cared for 1,333 soldiers and suffered only 73 deaths, which was the lowest mortality rate of any military hospital. The Robertson hospital, named for the judge who let Sally use one of his houses, returned 94 percent of its patients to service. Eventually Confederate authorities decided to close all private hospitals, declaring that soldier patients could only be cared for at government hospitals run by a commissioned officer with at least a rank of captain. When Tompkins heard the news, she

Captain Sally Tompkins

called on Jefferson Davis and asked for an exception to the new rule. Since her hospital's remarkable record spoke for itself, Davis commissioned Tompkins a Captain of Cavalry, unassigned, making Robertson Hospital an official government facility. She was the only female commissioned officer in the Confederate Army. As an unassigned officer she could remain at the hospital permanently. The military rank also allowed her to draw government rations for her patients, but she refused to be added to the army payroll.

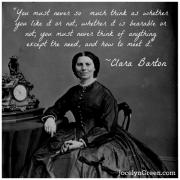

5) Clara Barton No list of groundbreaking nurses would be complete without her. Barton was fiercely independent, a self-appointed field-nurse for the Army of the Potomac. Working on her own, beyond the structure of the Sanitary Commission and Army Medical Department, she stockpiled supplies in her small Washington flat and then drove into the Virginia countryside, and into Maryland, to disperse them among the wounded. At General Butler's request, she cared for the soldiers in the Army of the James during the summer

Clara Barton

campaigns of 1864, as well. Her work for soldiers and their families didn't end along with the war, however. She continued her service by opening the Missing Soldiers’ Office in Washington, D.C. to help family members find the remains of their loved ones. By 1869, she had identified 22,000 missing men and received and responded to 63,182 letters from those trying to locate their soldiers. Later, Clara brought a chapter of the International Red Cross to life in America. For more in Clara Barton, click here.

~~~~~~~~

A Woman's Place

The following is excerpted from my nonfiction book, Stories of Faith and Courage from the Home Front, to explain why women had such struggles as nurses at the beginning of the war.

The clash between surgeons and women nurses which Georgeanna Woolsey described had its roots in how each group of people viewed the woman’s place in society. Americans in the mid-nineteen century commonly believed that men and women had their own separate spheres of activity. Men occupied the commercial, business and political fields. Women’s activities were relegated to home, church, women’s clubs and reform groups, and circles of female friends and relatives. But in which sphere did the hospital fall?

Normally, when someone fell ill, a doctor visited the home, examined the patient, and left the nursing care to the female relatives living in the household. Wives, sisters, daughters, and grandmothers administered medicine, dressed wounds, and saw to the patient’s recovery. The only people treated in the hospital were those who didn’t have women at home to nurse them. Once the war began, medical care for soldiers had to be systemized since the troops could not recover at home (although many wives and mothers travelled hundreds of miles to personally nurse their own wounded family members). Male doctors held that the ward was part of the military hospital, so it fell under their dominion.

Popular opinion also held that women would faint in the presence of war’s gruesome casualties, and that their innocence would be marred with exposure to the naked male body. Women nurses were convinced the hospital ward belonged in the female domain, since they were treating sick soldiers the same way they would in their own homes—and the home was unequivocally within the female sphere. More tension arose between men and women when the female nurses viewed the doctors’ advice as suggestions rather than strict orders, for at home, they had the freedom to follow or not follow the doctor’s orders as they saw fit. Over the course of the war, the surgeons and nurses came to accept and work with each other as both groups proved their mettle and shared genuine desire to save lives and speed recovery of the soldiers.

~~~~~

Wedded to War (Heroines Behind the Lines Civil War Book One)

Charlotte Waverly leaves a life of privilege, wealth–and confining expectations–to be one of the first female nurses for the Union Army. She quickly discovers that she’s fighting more than just the Rebellion by working in the hospitals. Corruption, harassment, and opposition from Northern doctors threaten to push her out of her new role. At the same time, her sweetheart disapproves of her shocking strength and independence, forcing her to make an impossible decision: Will she choose love and marriage, or duty to a cause that seems to be losing?

Find out more here.